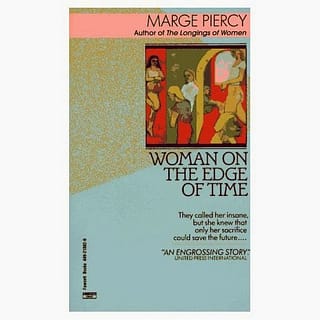

In her incredible novel Woman on the Edge of Time (1975), Piercy introduces the protagonist, Consuelo Ramos, during a quiet morning in her New York City apartment. Connie, as she is called by Anglos, gains the reader’s trust and compassion very early on in the novel when she stands up to her niece’s boyfriend-pimp, Geraldo, to protect her from having an abortion. Ramos’s protective outburst is violently turned against her and she is sent back to a mental institution—a feat disgustingly easy to perform by Geraldo who simply had to make up a story about Ramos’ attack to re-institutionalize her. The play of Geraldo’s privileged position against Ramos’ dominated one is palpable. Her return to the mental hospital causes her to reflect on and confront her previous time there, the loss of her daughter, and the structures of power that toss her about like so much flotsam on the surf. Much of the narrative unfolds within the mental institution as Ramos is shuffled back and forth between wards, and, ultimately, selected to take part in an emerging medical program to help patients control their violent tendencies. Piercy charts out, in almost Foucauldian manner, the interworkings of control of the mental hospital and its corollary, the medical industry. Perhaps, what Piercy does best is depict a protagonist who rests at the centre of a number of capillaries of power and forces for the reproduction of the present: on the one hand in terms of identity ethnicity, race, and gender; and, on the other the forces buffeting against such a subject in the 1970s United States racism, poverty, patriarchy, and mental illness.

In her incredible novel Woman on the Edge of Time (1975), Piercy introduces the protagonist, Consuelo Ramos, during a quiet morning in her New York City apartment. Connie, as she is called by Anglos, gains the reader’s trust and compassion very early on in the novel when she stands up to her niece’s boyfriend-pimp, Geraldo, to protect her from having an abortion. Ramos’s protective outburst is violently turned against her and she is sent back to a mental institution—a feat disgustingly easy to perform by Geraldo who simply had to make up a story about Ramos’ attack to re-institutionalize her. The play of Geraldo’s privileged position against Ramos’ dominated one is palpable. Her return to the mental hospital causes her to reflect on and confront her previous time there, the loss of her daughter, and the structures of power that toss her about like so much flotsam on the surf. Much of the narrative unfolds within the mental institution as Ramos is shuffled back and forth between wards, and, ultimately, selected to take part in an emerging medical program to help patients control their violent tendencies. Piercy charts out, in almost Foucauldian manner, the interworkings of control of the mental hospital and its corollary, the medical industry. Perhaps, what Piercy does best is depict a protagonist who rests at the centre of a number of capillaries of power and forces for the reproduction of the present: on the one hand in terms of identity ethnicity, race, and gender; and, on the other the forces buffeting against such a subject in the 1970s United States racism, poverty, patriarchy, and mental illness.The novel doesn’t simply operate on this register, however, as Woman on the Edge of Time works through a complex, indirect temporal relationship where the present constantly affects the dimensions of the future often read through memories of the past that we experience through Ramos. After the first chapter, and Ramos’s incarceration, the novel jumps back to the day before her niece had come to claim asylum with Ramos, the day she meets Luciente—a traveler from the future who is able to jump into Ramos time and also pull her forward into the future. Though it doesn’t appear to be explicitly about procreation, the novel serves to elaborate on Sheldon’s claims about the links between reproduction and futurity through its temporal dimensions.

With this introduction the reader begins another cluster of narratives in the novel, this time they are about the future. Luciente is from Mattapoisett, a utopian community in the future, which is interesting for its wide array of both sense of politics, radical and state administration: a mindful ecology and the abolition of gender, communal living and a more humane life style, the defeat of racism and the encouragement of art, the reconfiguration of the family and new life cycle rituals.[i]Ramos mediates this future through her shock and awe of it, for instance, she can’t believe children are raised by three parents all referred to as mother. In some sense, the novel repeatedly makes the same move in order to gauge Ramos’s reactions and offer patient explanations by the Mattapoisett utopians.

With this introduction the reader begins another cluster of narratives in the novel, this time they are about the future. Luciente is from Mattapoisett, a utopian community in the future, which is interesting for its wide array of both sense of politics, radical and state administration: a mindful ecology and the abolition of gender, communal living and a more humane life style, the defeat of racism and the encouragement of art, the reconfiguration of the family and new life cycle rituals.[i]Ramos mediates this future through her shock and awe of it, for instance, she can’t believe children are raised by three parents all referred to as mother. In some sense, the novel repeatedly makes the same move in order to gauge Ramos’s reactions and offer patient explanations by the Mattapoisett utopians.The utopians contact Ramos for a striking reason: their present is under threat and they reach her in the struggle for their own survival. The novel contains, at least, two major plot forces then, the impending surgery on Ramos in the mental institution in her own time, and the violent conflict between the utopians and their alternate future—one based on a continuation of the status quo. Herein lies the utopian politics of Piercy’s novel—the mediation is such that the winds of change blowing through Ramos time reach our own as well, the plea “we must fight to come to exist” (198) resonates with the present, only able to imagine radical difference and seemingly unable to activate it. What’s at stake for reading Woman on the Edge of Time alongside post-apocalyptic fiction, is the hindsight that the latter comes from a much more radical history than its conservative politics suggest.

The formal innovations of Piercy’s novel as well as its utopian politics make it a powerful tool to assess cultural forms predicated on the present’s connection to the future, like post-apocalyptic fiction. Indeed, the formal feature to stand out most prominently in my reading is the novel’s careful treatment of totality: Ramos mediates her past and the utopian future through her reactions to it and interpretation of it, indicating her complex and indirect connection to the future. While the time travel plot unfolds in this manner, the novel generates the background of mental illness and institutionalization that must also come to inflect any reading of the novel. We could attempt to map the multiple fields or zones of the novel, but to consider their relation to Ramos action in the world, and how one might move from one zone to the next is an intensely complicated task. I don’t wish to simply celebrate it for its complexity, but rather to consider the dynamic lesson that is generated by a novel that is concerned with changing the self-destructive path of the present in order to create an egalitarian future: this is no easy task; it requires hard work, dedication, and patience. The tension between the institutional and spatial immobility of Ramos and the temporal freedom that allows her to glimpse a radically egalitarian future makes Woman on the Edge of Time a novel both still worth reading and an excellent comparison to highlight how post-apocalyptic fiction functions differently today.

[i] These utopians run a balanced society. To get a partial sense of it one would need to read the novel as a summary of the changes, which only ends up sounding like a laundry list of radical demands from the left. Their use of language has changed drastically as a result of material changes as well, something else that intervenes between the reader, Ramos, and a full understanding of the utopia described. For instance, any gendered words are removed from the language immediately replaced by person or pers, and supplemented by a number of terms for one’s relation to others: sweet friend, coms (for co-mothers there are always three; men are mothers too in the future), etcetera.